How to look Medusa in the eye – or writing female rage into being

Why do we make monsters out of angry women? Turns out Medusa is pissed for good reason...

*This piece includes mention of sexual assault, mental illness and addiction. Take the time to consider whether this subject matter feels safe for your system right now, and if not, best to not read any further*

-

“Sometimes, I think, heroes are monsters and monsters are heroes”

- Natalie Haynes

There is a reason that monsters live under the bed. The bed is that place where sleep takes us over and we fall into the realm of the subconscious and dreams. Under the bed is the place even deeper than this, the place under our dreams. The dark, unseen void we have built a comfortable structure over. Monsters do not live peaceably in their own bounded territory far away, they are only ever found in close relationship with us, sleeping beneath us in the intimacy of our bedrooms.

The way a monster is depicted tells us what we fear in the most crude, embodied sense. It also shows us what we believe to be ‘heroic’. The overcoming of monstrosity is the essential narrative. We wish to see ourselves as saviours battling the monster out there. But what is the truth of the monster, what fears does she have to show us? In battling with the monster outside of us, we have committed ourselves to a sort of intentional blindness, and I believe it is feeding the very monster we wish to destroy.

My mother had a severe mental breakdown in 2018. She had been an alcoholic for many years, and her drunken monologues became increasingly delusional, vitriolic and disjointed. However, there were certain themes of these rants that I still can’t shake off, because they held uncomfortable truths. Spoken with such unnerving honesty, in a tone way beyond the bright walls of civilisation, her words could illuminate the darkest corners of our misogynistic history. Like waves reaching up towards moonlight in a storm, pausing for a celestial moment in the calm of their silvery height before crashing once more into the chaotic tempest of mental illness and addiction.

One such strand I wish to disentangle here is that society has made us look away from female rage, and even taught us to demonise it. I mean this in the most literal sense of turning the raging woman into a demon, a no-longer-human presence. Sometimes, it felt like my mother was challenging me to Stay With The Trouble, as Donna Haraway puts it, to not look away, to not shame a woman’s pain by recoiling in terror.

Listening to the radio, I hear a snippet of Stephen Fry telling a familiar Greek myth, that of Medusa. Only, he recounts it differently from the story I know. It was Poseidon who raped the young Medusa in the temple of Athena - not ‘mated with’ as in the Ovid translation - and the goddess was so outraged that she punished the victim by turning her into the snake-haired gorgon, eventually decapitated by the ‘hero’ Perseus.

A raped woman-turned-monster, punished for the ‘sacrilege’ of the act her body suffered, the crime committed against her transforming her into something non-human. This felt like the story my mother had been screaming out to me, the story of a history that lives within our bodies today.

To look into the eyes of this woman is to accept your own death by petrification. The organic process of petrification is to turn matter into stone. The emotional experience of feeling petrified is fear. The embodiment of petrification is paralysis, or the ‘freeze’ response. When a woman becomes ‘ugly’ by society’s standards because she carries the shame of what has happened to her, we become terrified of what will happen to us if we look directly into the eyes of this violence. There is some ancient idea that staying too close to the effect of violence will transform us by proxy. Is this monster condition contagious? If we touch the trauma do we become it? So, we turn away and re-write the story as one of separation - one of monsters and heroes.

For this violent death by petrification to take place, the so-called victim must make eye contact with Medusa, quite literally looking the trauma in the eye. The story goes that her gaze would turn you to stone, immortalised and frozen in form but no longer living.

My mind now changed about the personal history of this gorgon, and feeling the deep sorrow of a person having been sexually assaulted then committed to a life without eye contact, I read further into the myth. Looking her straight in the eye, she returns my gaze and tells me a different story…

Whilst Medusa was alive, there is no written instance of her turning people to stone. It was only when she dies that her dismembered head was used by Perseus as a weapon of war to petrify his enemies. She was made pregnant by the rape of Poseidon, and was with twins when Perseus decapitated her – hardly a heroic move, murdering a lone woman pregnant with twins, monstrous or otherwise. And it is her death that sparks a legacy that captured my imagination. Her dismembered body and her spilled blood become fertile sources of life, creation and healing.

Upon her murder, her children Pegasus – the winged horse-God - and Chyrsaor - a giant wielding a golden sword - sprang to life from her body, from her blood. The horse and the golden blade are associated with the ocean, the domain of their father Poseidon. But also of the unconscious and wild, untamed feminine power.

Whilst Perseus is in Ethiopia rescuing the princess Andromeda who would become his wife, Medusa’s head lay on the shore, her blood spilling into the Red Sea supposedly creating the coral reefs that now lie at the bottom of one of the warmest deep-sea environments in the world. Spilt drops of her blood elsewhere created the venomous vipers of the Sahara. And as Perseus flew over Libya with her head, out dropped more blood that became the Amphisbaena – the dragon-like ant-eating serpent with a head at each end. Amphis means ‘both ways’ and baene means ‘to go’.

Mythological serpents are documented in cultural history across the world and they are almost always associated with water, transformation and paradox. They change whilst remaining the same. The thousand-headed serpent Shesha in Hindu mythology floats on the Ocean of Milk, said to hold every planet in the universe within its hoods. The Ouroboros swallows its own tail with its mouth, an enduring image of the cycle of life. The Amphisbaena is the embodiment of going both ways. Medusa herself was both victim and aggressor, a beautiful young woman and terrifying monster. When Athena transformed Medusa’s hair into living snakes, she is taken beyond both the gender binary and the separation between nature and culture. She is in the realm of the serpent, the queer, the animal, the supernatural.

When presented with the murdered Medusa’s head, Athena took two drops of her blood one from the left side and one from the right. The drop from the left is a deadly poison, but the drop from the right has the power to resurrect the dead. Her body a container for the binary of life and death, a powerful part of our lineage of healing. When the god of healing Aesclepius is learning the medicinal arts, Athena gives him these two drops of blood to be used in his work. Is it a coincidence that once established as an authority in healing, Aesclepius carries with him a staff entwined with two serpents?

The gorgon head existed way before this myth, as mundane sculpture adorned outside people’s homes in ancient Greece. These talismans were a form of protective magic and were stranger and more animalistic than the images of Medusa you or I may be familiar with. The serpent hair looks more like a lion’s mane, the mouths open wide with lolling tongues suggesting loud noise emanating from them. Some depictions even had tusks, like those of the wild boar. They are evocative of the wild, unpredictable, violent forces of the natural world, which society back then had to contend with in a much more immediate sense than we do today. They were a mirror of the forces that people needed protection from, an offering of recognition, a symbol of our own capacity for wild rage when we need to defend what matters most to us.

.The word Medusa means ‘guardian’ or ‘protector’. There is no consensus on the original meaning of ‘gorgon’ but is connected to ‘thunder’; Medusa’s horse-God child Pegasus carried on this lineage and became messenger of the thunderbolt to Zeus. Classicist, writer and comedian Natalie Hayes believes the gorgons were considered monstrous because they were females being loud. The loud woman screaming of a bodily invasion, of injustice, of her own pain, silenced into monstrosity and stuffed into a binary. I am reminded of the words of Audre Lorde: “Your silence will not protect you”. Lorde believed wholeheartedly in the power of language to confront injustice. The gorgons were not afraid of making big sounds, or of using their voice as a weapon. But their cries were unintelligible, animal roars of which humans couldn’t decipher.

Was it a case of being misunderstood that transformed her from protector to monster? Or is this the fine line that women tread every day? The impossible project of meeting the conflicting demands society puts on women: protect yourself but don’t be ugly, animalistic, or ‘unfeminine’ in the process. There is a line, and every woman will have sensed a moment when they’ve crossed it.

When a structure of belonging becomes one of securitisation it needs relational bonds based on fear to tie a community together. This means the group needs a monstrous other to continually defend themselves from, in order to bond and maintain societal cohesion. Securitisation is about turning a threat into an existential problem and allows for extraordinary measures to be taken in the name of security. Once an existential threat is established as essential for a social bond to be maintained, it becomes terrifying for us to look at that threat with any nuance because it feels as if changing our minds will result in the annihilation of our community. And our community is as essential for our survival as food, water and shelter, no matter what story late-capitalist individualism pedals. In this context, it is essential for survival that the monster remains misunderstood.

The demonisation of Medusa is about the way we bond as a society, and what we decide we cannot look at. She is the embodiment of what happens when we live hierarchically – we need to be in some state of permanent denial. She symbolises a rejection of the idea that we are nature. The snakes are not adjunct to her being, they are her body. As rational thought began to take hold in the patriarchal psyche of Ancient Greece, the decapitated head becomes a character, whilst the body – like Medusa’s – is discarded into the margins, storyless.

Medusa’s is a story of a silenced voice. The lineage of my mother and my grandmothers is not only one of addiction and mental illness, but also one of silencing and looking away. I wonder how many of us have a similar ancestral wound, that of the voiceless woman with no mentor to guide her to her story: misunderstood and rejected as an existential threat to society.

This is not just about giving voice to the pain but to the fullness of a woman’s experience and what that story looks like when we remove the (internal and external) patriarchal judgement that so often accompanies any public woman’s voice. In an essay entitled The Laugh of the Medusa, French feminist philosopher Cixous explores a re-writing of Medusa as beautiful, desirous, and laughing. “Write yourself,” she says, “Your body must be heard. Only then will the immense resources of the unconscious spring forward”

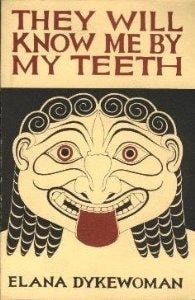

Medusa has become an icon of power and female rage. An older image of the gorgon emboldening the front cover of the famous book of lesbian poetry They Will Know Me By My Teeth. Gianni Versace chose Medusa’s head as the company’s logo to represent the duality of opulence and boldness that the brand came to be known for. The image of her head is an enduring one, but the story of her body, her wholeness, remains to be known.

I wonder what would happen if we humanised female rage and dared to hold its gaze? I wonder what it would tell us about how enslaved we are by what we imagine people will think of us, and the weight of denial we carry from generation to generation?

Medusa tells me of the strength and power that comes from rejection. Because what is rejected is not always the thing that is not good enough. What is rejected is sometimes the stuff that society is not ready to listen to or see, and therefore a radical, rebellious site of knowledge.

She teaches me to embrace my own paradox and all the seeming contradictions within me. She reminds me that I am nature, and that nature is a wild, unpredictable force of energy. My loudness is simply a part of my wholeness and needn’t be pathologized, demonised or even always political. Sometimes, I am loud because I feel pleasure, passion, and aliveness. She teaches me to be fearless in my anger and not feel ashamed of how I may be judged because my anger may have something profoundly honest baked within. She reminds me that truly believing in a woman’s voice is feminism, and that I must keep writing.

What I was reading, and listening to, for this piece:

Hélène Cixous – The Laugh of the Medusa

Madam Medusa – UB40 – thank you to Helen for sharing this track with me

Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene by Donna Haraway